The International New York Times

August 14, 2015

by Vanessa Barbara

Contributing Op-Ed Writer

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — Last month, a man was beaten to death by a mob after being accused of trying to rob a bar in São Luís do Maranhão, in northern Brazil. The man, Cleidenilson Pereira da Silva, was stripped naked by the crowd, tied to a pole, kicked, punched and hit with stones and bottles. He died at the scene.

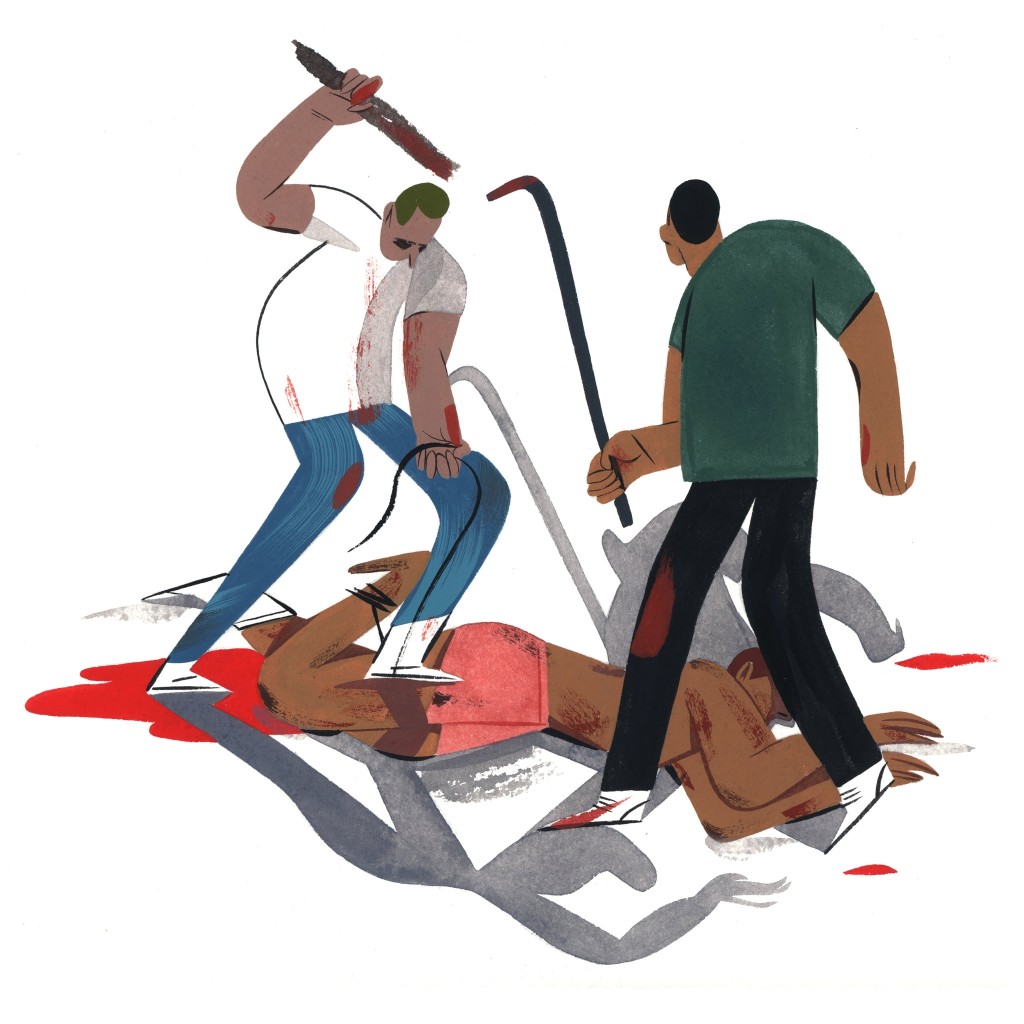

At least 20 people took part in the lynching, which was not the only one in Brazil that month. A few days after that attack, a man in metropolitan Belo Horizonte was dragged through the street by a mob and fatally beaten with a piece of wood for allegedly stealing a cellphone. On the same day, in a district nearby, another man died after being stoned by a crowd. He had been accused of attempted robbery.

There is at least one lynching attempt per day in Brazil, according to the sociologist José de Souza Martins, who recently published a book on the subject. In the period since 2011, he reported 2,505 lynching episodes, many of them in the state of São Paulo. According to Mr. Martins, lynching has become part of Brazilian social reality. There is even some public support for the notion of “mob justice.”

Last year, a news anchor said on national television that the severe beating of a black teenager in Rio de Janeiro was “understandable.” After being accused of mugging a pedestrian, the boy had his clothes torn and was tied to a post by the neck with a bicycle lock. Firefighters had to use a blowtorch to free him. “Since the local government is weak, the police demoralized and the legal system a failure, what is left to the good citizen but to defend himself?” the newscaster, Rachel Sheherazade, asked. She said she considered the attack a kind of “collective self-defense.”

Brazil’s public prosecutor’s office filed a civil complaint against the TV network where Ms. Sheherazade works, accusing her of violating human dignity and of calling on people to take the law into their own hands.

But many Brazilians seemed to agree with her, and praised the punishment, happily sharing on social networks the picture of the boy tied to the post. A newspaper tracked the comments about this subject on its Facebook page and verified that 71 percent of them supported the lynching.

The rash of vigilante justice continued even when, a few months later, a woman was beaten and later died because of a false Facebook rumor. A local gossip page on Facebook had accused a woman of performing black magic rituals on kidnapped children, and posted a police sketch of an alleged suspect. Though the local police denied the rumor, stating that there were no records of missing children in the area, the woman, Fabiane Maria de Jesus, a mother of two, was killed by a violent mob who thought she resembled the suspect.

In an interview with an online magazine, Mr. Martins said that the lynchings were, in part, a result of social contagion: The more publicity they gain, the more they tend to occur. “The transformation of crime into a spectacle for media and social networks has been a likely multiplication factor in the number of lynchings,” he said. “The emotional news service, which is often also superficial and uninformed, encourages the spread of this practice.”

During the beatings, he said, there is a certain progression in the actions of the crowd: First they attack the victim with rocks, bottles and pieces of wood, and then, more directly, with kicks and punches. In this escalating violence, there were cases in which eyes were gouged out, and ears cut off; people castrated or buried alive. The atrocities have been worse in cases where the victims were black. Later, the aggressors tend to explain away their actions by resorting to notions of justice and crime control, denouncing the absence of effective policing and a rigorous criminal justice system. The mobs don’t acknowledge that they are motivated by hatred and prejudice.

But this sense of righteousness is misleading, in many ways. People can be quickly riled up for the most trivial reasons when they become part of a mob. Last year, I witnessed a tense situation in downtown São Paulo, when a man with bipolar disorder climbed on the roof of a bus, undressed and started to provoke the crowd. Some pedestrians threatened to beat him up with sticks and brooms, indignant that he was disturbing traffic. Luckily the police arrived, and the man was brought down without incident.

It doesn’t take much to ignite a mob. Sometimes, a diffuse hatred or a strong disbelief in the criminal justice system is misdirected at whoever is available. Some lynching cases involved victims who resembled another person. In an emblematic case last year in São Paulo, a history teacher was running in the street when somebody wrongly identified him as the man who had just robbed a bar; a mob chained him and tried to break his legs. He was eventually spared after giving a three-minute lecture on the French Revolution, reassuring them that he was a productive member of society, not a thief.

Members of a violent mob who summarily execute a person often consider themselves good and law-abiding citizens, as opposed to deviants or delinquents who deserve to be punished. Their mottos are: “the only good thief is a dead thief” and “human rights are for right humans.” They sometimes have the perception that the law protects criminals, and that therefore it may be useless to appeal to the established channels when it comes to fighting wrongdoing. (In a paradoxical detail, a uniformed policeman is clearly visible in the footage of the lynching in Maranhão, just watching and recording it with his cellphone.)

By pretending to command justice, mobs usually end up putting themselves beyond justice. Some of the aggressors who tied the boy to a post with a bicycle lock were later found to be suspects in other crimes such as drug trafficking, robbery, car theft and rape.

So much for the good citizens.