Tourists with a pink dolphin in the Amazon River in Brazil.

Credit: Flavio Varricchio/Brazil Photos, via LightRocket, via Getty Images

The New York Times

April 21, 2017

by Vanessa Barbara

Contributing opinion writer

MANAUS, Brazil — The “encontro das águas” (meeting of waters) between the dark Negro River and the light-brown Solimões River is impressive. No wonder it’s one of the main tourist attractions near the city of Manaus, capital of the state of Amazonas. For several miles, the two gigantic rivers flow side by side without mixing because of their difference in water composition, flow rate and density. (You can feel the variation of temperature by putting your hand in the water as the boat crosses the visually distinct line.) When the Negro and the Solimões finally merge, they form the Amazon, the world’s largest river by discharge of water and one of the longest.

When I recently went on a boat tour in the Janauari Ecological Reserve, near the meeting of waters, the boatman asked if I would also like to visit a family of ribeirinhos (riverside dwellers) who have a caiman, a sloth and a snake. “You can take selfies with the animals, and later give them some gratification,” he told me, euphemistically suggesting tips for the people who keep the animals. I vociferously declined.

We resumed our navigation on the small motorboat through cool, peaceful igarapés (forest streams) leading to dazzling igapós (swampy, flooded forests). It seemed as if a dam had ruptured somewhere and the place was about to be submerged. Trees as high as buildings were half drowned by the river. The boatman became less talkative, as if I’d offended him by refusing his last offer. I enjoyed the scenery; there was no need to hug illegally domesticated sloths.

Brazil still has a long way to go in the field of ecotourism. While in some places, as on the island of Fernando de Noronha, in the northeast, the rules concerning wildlife preservation are strict, in others there is less attention to long-term conservation and the ecological and social impact of tourism, often leading to the pure and simple exploitation of animals, as well as local people and their cultures.

One of the most profitable tourist activities in the Amazon is swimming alongside pink dolphins or feeding them from a flutuante, a private floating deck, often situated within a national park. Tourists regularly ride, restrain and harass the dolphins. Some even lift them out of the water for photographs. (Sometimes this is done with the encouragement of a tour guide.) There are accounts of people being accidentally bitten, and on one occasion, a man retaliated by punching the dolphin.

A few years ago, a commission of federal agencies and research institutes issued local guidelines for the activity — including the amount of food to be offered and the requirement that only tour guides could feed the dolphins — but few people adhere to them. According to the owner of one flutuante, tourists must only avoid touching the dolphin’s blowhole. (Please!)

There’s no federal legislation prohibiting feeding and touching the dolphins. As a result, their behavior has already changed: Many now survive on the frozen fish provided by tourism groups. They’re also conditioned to stay close to the flutuantes and to humans. According to researchers, aggression is now common among the dolphins.

Another popular activity in the Brazilian Amazon is caiman-spotting. In the evening, groups of people cruise the riverbanks, seeking out the huge nocturnal lizards that resemble crocodiles. It wouldn’t be disruptive if so many guides didn’t make a point of jumping in the water to grab the caimans and hold them up for photos.

Amazon tour operators also offer recreational fishing of piranha, the omnivorous fish with sharp teeth and a ferocious reputation, and fake fishing of pirarucu, an ancient, giant fish that is at risk of extinction. The latter takes place in enclosed water tanks. In some ways, it’s better because the pirarucus aren’t injured by hooks, only mildly harassed by tourists trying to lift them out of the water.

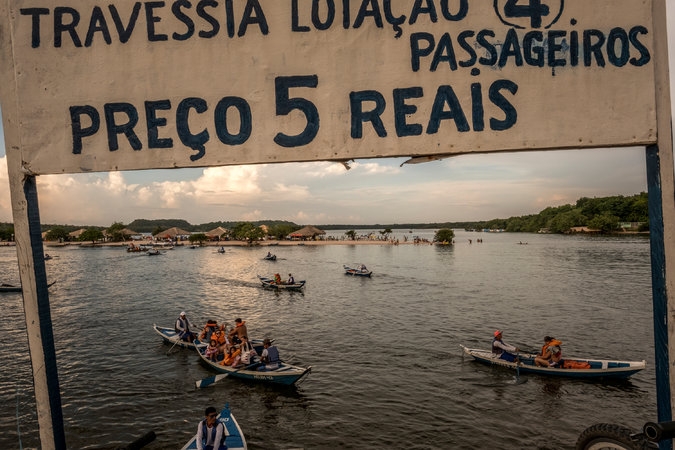

Alter do Chao has grown in popularity with Brazilian and foreign tourists in recent years, earning itself the nickname the “Caribbean of the Amazon,” leading some to worry about over development, and its environmental impact on the fragile ecosystem. Credit: Bryan Denton for The New York Times

All of these activities take advantage of a lack of clear laws governing ecotourism and the use of natural resources. Tour operators promote packages by using questionable environmentalist phrases. One advertises “ecological fishing”; another promises to have the federal environmental agency’s authorization to take tourists swimming with dolphins. That’s enough for most people visiting the Amazon — even if it’s not true. The local people who keep wild animals as pets to lure tourists often claim that they release the animals at night and recapture them in the morning.

Animals are not the only ones being abused. Another popular activity in Manaus is a visit to an indigenous community formed by five ethnic groups (Dessana, Tukana, Tuyuca, Wanana and Tatuia), which some tour operators deceitfully describe as a “tribe.” Since the beginning of the last century, the indigenous people, who are perhaps Brazil’s most marginalized and impoverished population, have migrated (or been expelled) from their original lands. (And I’m talking only about the small remnant left after the genocides that started with the arrival of the Portuguese.) They stage traditional music and dance performances for the guests of expensive jungle lodges.

Indigenous people are often forced by their employers to meet tourists’ stereotypes: the romantic, noble savage with slightly frightening rituals and no refrigerator. But that’s not the worst part. Indigenous people didn’t know that some of their bosses have traditional practices of their own: For five years, 34 Tariano people worked for a jungle lodge in exchange for only leftover food and a collective paycheck of $30 per performance. Others are not even paid and instead rely on selling handicrafts and jewelry to the visitors. There is no industry-standard agreement on the fair share of revenues for indigenous groups, and again, no federal regulation. It seems nothing will change until indigenous people themselves have the means to control all aspects of the experience they offer to tourists — and also reap the profits.

On the other hand, many jungle lodges and tour operators are becoming more aware of these issues. Environmentally conscious tourists are also pushing for changes. The sustainable Uakari Lodge in the Mamirauá Reserve, for example, is run by members of the local community. So maybe there is some progress.

In another jungle lodge called Anavilhanas, better attuned to an environmental conscience, I’ve enjoyed the most jaw-dropping tour of my trip: a simple kayak expedition through igarapés and igapós, stopping here and there to watch birds, monkeys and spiders at a distance. In the Amazon, there’s no need to do more than that.

Vanessa Barbara, a contributing opinion writer, is the author of two novels and two nonfiction books in Portuguese.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on April 21, 2017, on Page A11 of the National edition with the headline: Don’t punch the dolphins.