We live in a time of more questions than answers. Beware anyone who thinks otherwise, especially presidents.

The New York Times

Apr. 14, 2020

by Vanessa Barbara

Contributing Opinion Op-ed Writer

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — My first symptoms started on a Monday morning, March 23. I was just getting over a random disease that my daughter had brought home from nursery school — we’re still not sure what — when I had a sudden fever. My husband was the culprit, we decided; my daughter and I had already been isolated at home sick with something else for 10 days. He, on the other hand, was still attending a few work meetings and leaving our house to buy groceries.

On that first day, I had a low fever and a strong headache. I also lost my sense of smell and developed nausea and ear pain. I called an ear, nose and throat doctor and reported my symptoms; she asked to examine me at the hospital. On Tuesday, I went to see her — she looked like an astronaut, in all her protective gear — and she promptly ruled out a bacterial infection. She prescribed a fever reducer and a medication to loosen the mucus. Then she put me on home quarantine — again — this time, for a suspected case of Covid-19.

In Brazil, until very recently, only the most severe cases were being tested for the new coronavirus. So I spent the next week in a haze: Was it Covid or not Covid? Would I infect my 21-month-old daughter? How could I take care of her in such a dire state? Would I soon require hospitalization? I was already feeling depleted from the intense mothering of the past couple of days without nursery school; suddenly I had to keep doing exactly the same thing, but with a fever. I wondered about the recovery rates for exhausted moms.

At the same time that I was facing this unprecedented uncertainty and fear, my president seemed absolutely certain — about everything.

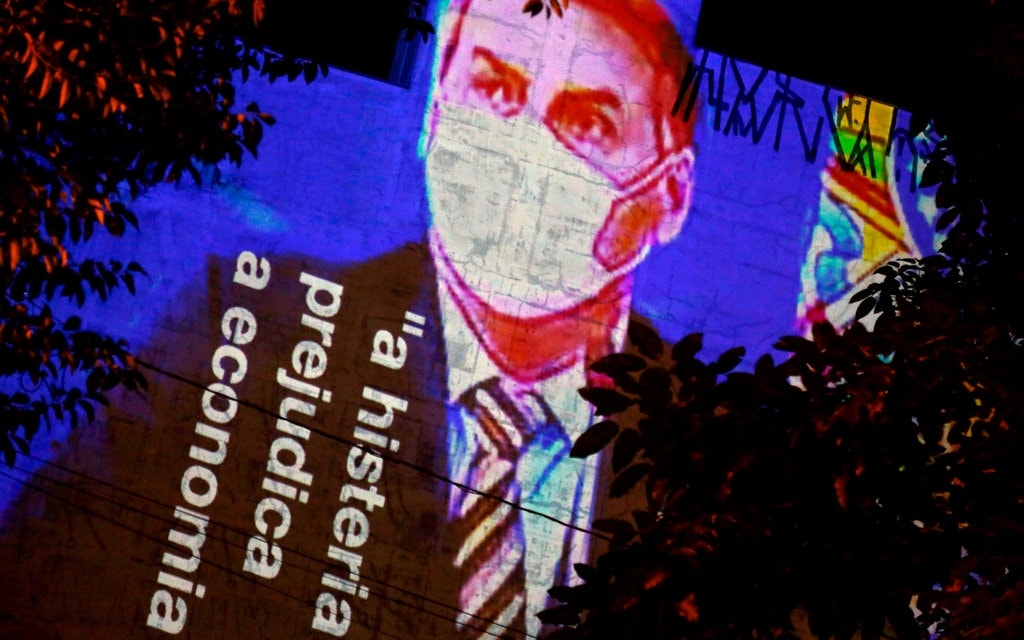

For weeks now, President Jair Bolsonaro has been downplaying the severity of the coronavirus crisis; he dismissed the outbreak as a “fantasy,” called measures to fight it “hysteria” and called the illness a “measly cold.” He spreads dangerous misinformation — about an unproven cure, for example — and publicly ridicules quarantine measures. He ignores statistics, scientific evidence and specialists’ recommendations, as if he alone is endowed with a mysterious source of wisdom. He acts with the assuredness of fools. When in mid-March, Brazilian governors and mayors started to enforce lockdown measures, Mr. Bolsonaro accused them of falling into a state of panic. “Our lives have to continue,” he said, urging everyone to roll back restrictions. Later, he conceded a little ground, saying that “we will all die one day.” Because that is the sort of statesman he is.

Luckily, most of us haven’t listened to the president. In fact, few are still listening to him. My city, São Paulo, has been the place hardest hit by the outbreak in Brazil, and that’s enough to keep us on our toes — there’s no time to pay attention to delirious statements like Mr. Bolsonaro’s call for a national day of fasting and prayer to “free Brazil from this evil.” He is becoming more isolated by the day — figuratively, I mean: The approval ratings of his minister of health and various state governors are on the rise, while his own have plummeted.

Back in the realm of reality, the weekend came and my fever subsided, but I still had a persistent headache. I knew by then that the second week of the disease cycle was the truly critical one, when patients either improve or get sicker. I tried not to have a panic attack, since if I did, I wouldn’t know how to know whether it was the disease causing shortness of breath or my intense anxiety. At this point, the country had registered 4,309 confirmed cases and 139 deaths — 98 of them in the state of São Paulo.

On Tuesday, the 31st, I managed to schedule a visit with a health care provider to test me for the coronavirus. (I had to pay $73 for it.) It was the RRT-PCR test, which stands for real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; the test detects bits of viral genetic material present in respiratory secretions. The results would not be ready for a couple of days. By then, my headache had lessened to something more tolerable, and I could once again smell the sweet scent of my daughter’s full diaper. I recovered my appetite (not while in proximity to her diaper, though). We resumed our mother-and-daughter sessions of crazy tap dancing on the balcony. I felt a vague sense of victory. By Friday, April 3, Brazil had 9,216 confirmed cases and 365 deaths.

Then on Saturday, the 4th, my test results came back negative. And the uncertainty came flooding back: Had it been the flu all this time? Or a false negative, perhaps? (A Chinese study has suggested that the false-negative rate of PCR tests may be around 30 percent.) A positive result would have been at least something concrete to deal with, a rare certainty amid all this coronavirus-fueled anxiety. As the days pass, I’m left wondering when or if we will get serological tests — which detect the presence of antibodies for a specific disease — to settle the question. I was back where I’d started, only more exhausted this time and with a (slightly improved) headache.

Besides the terrible loss of thousands of lives, the coronavirus has hit us with a wave of uncertainty. We worry for ourselves and for our parents. We wonder what will happen next, when the curve will start to flatten, how long this is going to last. Mass testing of the population still seems the surest and fastest way to stop the virus, but when my turn came, I learned that even this is riddled with ambiguities. But perhaps at this time, only fools have certainty about anything.

Vanessa Barbara is the editor of the literary website A Hortaliça, the author of two novels and two nonfiction books in Portuguese, and a contributing opinion writer.