Welcome to the wonderful, threatened world of Brazil’s “quilo” restaurants

The New York Times

Oct. 25, 2020

by Vanessa Barbara

Contributing Opinion Op-ed Writer

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — The Swedes gave the world the concept of “smorgasbord,” a celebratory buffet meal featuring a variety of hot and cold dishes. But it was the Brazilians who elevated this gastronomic mishmash to a new level. By adding a singular touch of inventiveness, recurrence and chaos, they gave the world something special: the “quilo” restaurant.

Such restaurants may look familiar — in form and method, they’re perhaps not too far from a cafeteria, Korean deli or salad bar. But they are deeply expressive of a specifically Brazilian approach to food: communal, yet with full rein for individual creativity; workaday, yet luxuriously varied. And very, very delicious.

They amount to a vital tradition at the heart — and in the stomach — of the country’s culinary culture. Now the pandemic, which has wreaked terrible havoc on Brazil, threatens to disrupt and perhaps destroy them.

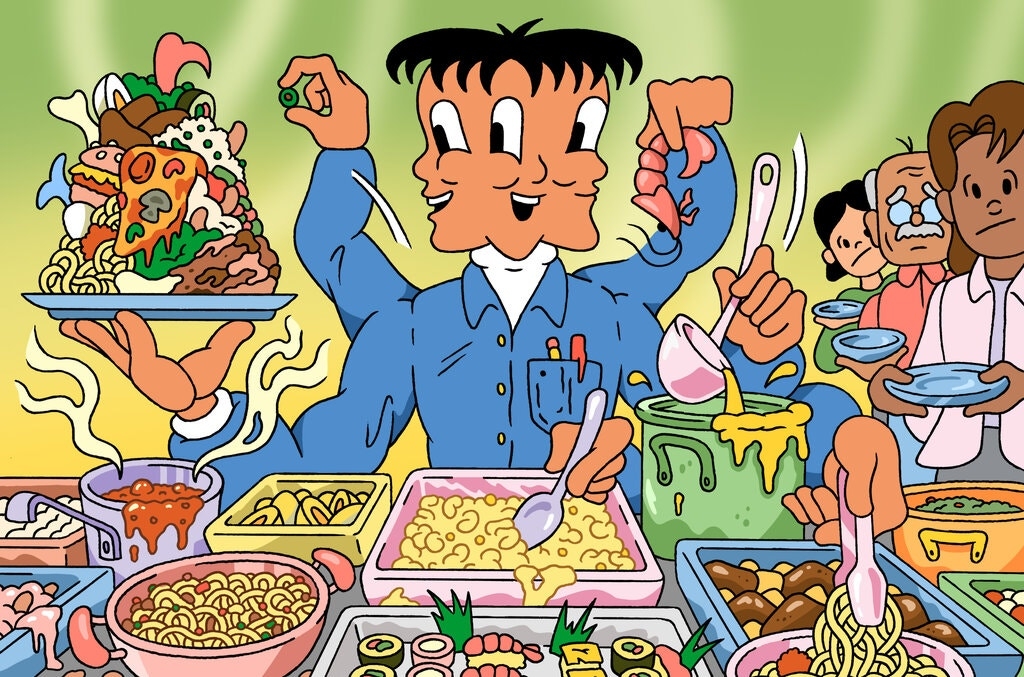

As soon as customers walk into a quilo restaurant, the magic starts. They aren’t ushered to a fancy table by a waiter — they pick up their plates from a pile and enter a line. Then they serve themselves from an extensive array of dishes, including (but not limited to) soup, rice, beans, eggs, steak, pork, seafood stew, shrimp bobó, lasagna, pizza, yakisoba, kebabs, grilled cheese, crab-stuffed shells, sfihas, tabbouleh, quiches, ceviches, barbecue and sushi. They top their plates with a slice of mango or a proud piece of watermelon and go to the scales. That’s when they find out how much they’re going to pay.

While the original Swedish smorgasbord is a celebratory meal with formal rules of etiquette, quilo restaurants are part of everyday life. Inexpensive and found on street corners all over the country, they serve home-style meals for workers on a short lunch break. They typically charge around $10 per kilogram (that’s why they’re called “quilo” — “kilo” in English), or 35 ounces, and they are often open only for a quick lunch.

But that doesn’t mean that there are no rules. You can’t jump the line or use the spoon for the shrimp to scoop up the mashed potatoes. (Not nice, really.) And it is not considered polite to disrupt the progress of the line in order to go back and pick up more quail eggs.

Apart from that, there’s no gastronomic judgment. Everything is permitted.

At least it was — before the pandemic. There was a time when co-workers went to a quilo restaurant and chatted over the chafing dishes, picking at the food with a spoon and airing lots of talk about the nutritional value of broccoli. Everybody gave their opinion about it, saliva droplets and all. On their plates, you could marvel at the combination of papaya with sushi, coated in a full-bodied sauce of measles morbillivirus and Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria. Or a good strain of the H1N1 virus perfectly paired with beef Bourguignon. It was all part of the game.

“There is a Brazilian tradition of eating directly from the pots on the stove,” Mary Del Priore, a historian, recently told Vejamagazine. “Quilo restaurants refer exactly to that.” People gladly used the utensils that dozens of others had used before. They laid a spoonful of stew on their plate, then changed their mind and put it back. The feijoada would remain out on the counter, exposed and disordered, open to all.

Not anymore. Now in many quilo restaurants, an employee must serve the clients — killing all the joy of jumbling food together in an open buffet. In other restaurants, customers can serve themselves, but only if they wear plastic gloves, lending the activity a tasteless, antiseptic feel. They must also socially distance in the line and under no circumstances share a table with strangers. A rich, hectic atmosphere has been replaced with something transactional and detached.

Many quilo restaurants have started to limit their offerings. Diners cannot choose anymore from 20 kinds of salad, 25 hot dishes, three types of raw fish and 10 desserts — as if the food counter were a gastronomic reflection of Brazil’s social and ethnic diversity. (Sashimi with spaghetti, falafel with paella, empanadas with sardines … you get the idea.) Now we’re as homogeneous as can be.

And it gets worse: Many quilo restaurants are slowly transitioning to offering only regular, à la carte meals. That’s terrible news for vegans and vegetarians, who will be unable to set up a nutritious, colorful plate with only rice, grains and vegetables.

I know: We’re dealing with a deadly public health emergency, and some things need to change if our beloved quilorestaurants are not to become superspreader locations. People’s lives, in a country where over 150,000 have already been lost to the virus, are more important than immersive buffet experiences.

I know, I know. But I’m going to miss my meal of rice and beans with spiced eggplant Parmesan, creamed corn, cabbage, cucumber, deep-fried cassava and a slice of pineapple to top it off. For a people who have never been stopped, not even by their indigestion, it is a sad fate.

Vanessa Barbara is the editor of the literary website A Hortaliça, the author of two novels and two nonfiction books in Portuguese, and a contributing opinion writer. A version of this article appears in print on Oct. 26, 2020, Section A, Page 23 of the New York edition with the headline: Sashimi With Spaghetti? Yes, Please.