The New York Times

May 27, 2021

by Vanessa Barbara

Contributing Opinion Writer

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — It’s not often that a congressional inquiry can lift your spirits. But the Brazilian Senate’s investigation into the government’s management of the pandemic, which began on April 27 and has riveted my attention for weeks, does just that.

As the pandemic continues to rage through the country, claiming around 2,000 lives a day, the inquiry offers the chance to hold President Jair Bolsonaro’s government to account. (Sort of.) It’s also a great distraction from grim reality. Livestreamed online and broadcast by TV Senado, the inquiry is a weirdly fascinating display of evasion, ineptitude and outright lies.

Here’s one example of the kind of intrigue on offer. In March last year, as the pandemic was unfurling, a social media campaign called “Brazil Can’t Stop” was launched by the president’s communications unit. Urging people not to change their routines, the campaign claimed that “coronavirus deaths among adults and young people are rare.” The heavily criticized campaign was eventually banned by a federal judge and largely forgotten.

Then the plot thickened. The government’s former communications director, Fabio Wajngarten, told the inquiry that he didn’t know “for sure” who had been responsible for the campaign. Later, stumbling over his words, he seemed to remember that his department had developed the campaign — in the spirit of experimentation, of course — which was then launched without authorization. A senator called for the arrest of Mr. Wajngarten, who threw a contemplative, almost poetic glance to the horizon. The camera even tried to zoom in. It was wild.

That’s just one episode; no wonder the inquiry holds the attention of many Brazilians. So far, we have been treated to testimony from three former health ministers — one of them had major issues with his mask, inspiring countless memes — as well as the head of Brazil’s federal health regulator, the former foreign minister, the former communications director and the regional manager of the pharmaceutical company Pfizer.

The upshot of their accounts is obvious, yet still totally outrageous: President Jair Bolsonaro apparently intended to lead the country to herd immunity by natural infection, whatever the consequences. That means — assuming a fatality rate of around 1 percent and taking 70 percent infection as a tentative threshold for herd immunity — that Mr. Bolsonaro effectively planned for at least 1.4 million deaths in Brazil. From his perspective, the 450,000 Brazilians already killed by Covid-19 must look like a job not even half-done.

Spelled out this way, the effort looks shocking. But to Brazilians living under Mr. Bolsonaro’s rule it’s hardly surprising. After all, the president seemed to do everything he could to facilitate the spread of the virus. He has spent the last year speaking and acting against all scientifically proven measures to curb the spread of the virus. Social distancing, he said, was for “idiots.” Masks were “fiction.” And vaccines can turn you into a crocodile.

Then there was the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, which Mr. Bolsonaro promoted as an early treatment and miracle cure for Covid-19 — despite all scientific evidence to the contrary and the express advice of two former health ministers. During the inquiry, two different witnesses somberly confirmed that they had seen the draft of a presidential decree stipulating that the drug’s leaflet should be changed to include its use against Covid-19.

It gets worse. According to both Mr. Wajngarten and Carlos Murillo, the regional manager of Pfizer, the pharmaceutical company repeatedly offered to sell its Covid-19 vaccine to Brazil’s government between August and November last year — but got no answer at all. (Perhaps the health ministry had more important things to do, like learning how to properly use masks.) Considering that Brazil was one of the first countries to be approached by the company, a quick response would have secured Brazilians as many as 1.5 million doses at the end of 2020, with 17 million more in the first half of 2021.

Instead, after turning down another three offers the government eventually signed a contract in March, a staggering seven months after the first offer. The first one million doses arrived in late April. The rollout, as a result of the government’s negligence in securing vaccines, has been halting, with regular shortages of shots and a lack of supplies leading to delays in production.

I wonder if it was all part of the plan. When Gen. Eduardo Pazuello, Brazil’s health minister between May 2020 and March 2021, was asked why the Ministry of Health requested the lowest amount of vaccine doses from Covax, the World Health Organization’s vaccine-sharing initiative — they could have asked for enough doses to immunize as much as 50 percent of the population, but preferred to go for 10 percent — he didn’t even blink. The process, he explained airily, was too risky and the vaccines too expensive. So that’s that.

It seems ever more clear that herd immunity, through obstruction, disinformation and negligence, was always the aim. The bitter irony is that it may be impossible to attain. In Manaus, where 76 percent of the population had been infected by October, the result was not herd immunity: It was a new variant.

The inquiry, slowly and steadily, is unveiling a classic supervillain plot, at once nefarious and absurd, deadly and appalling. Whether the villain meets his comeuppance is another story.

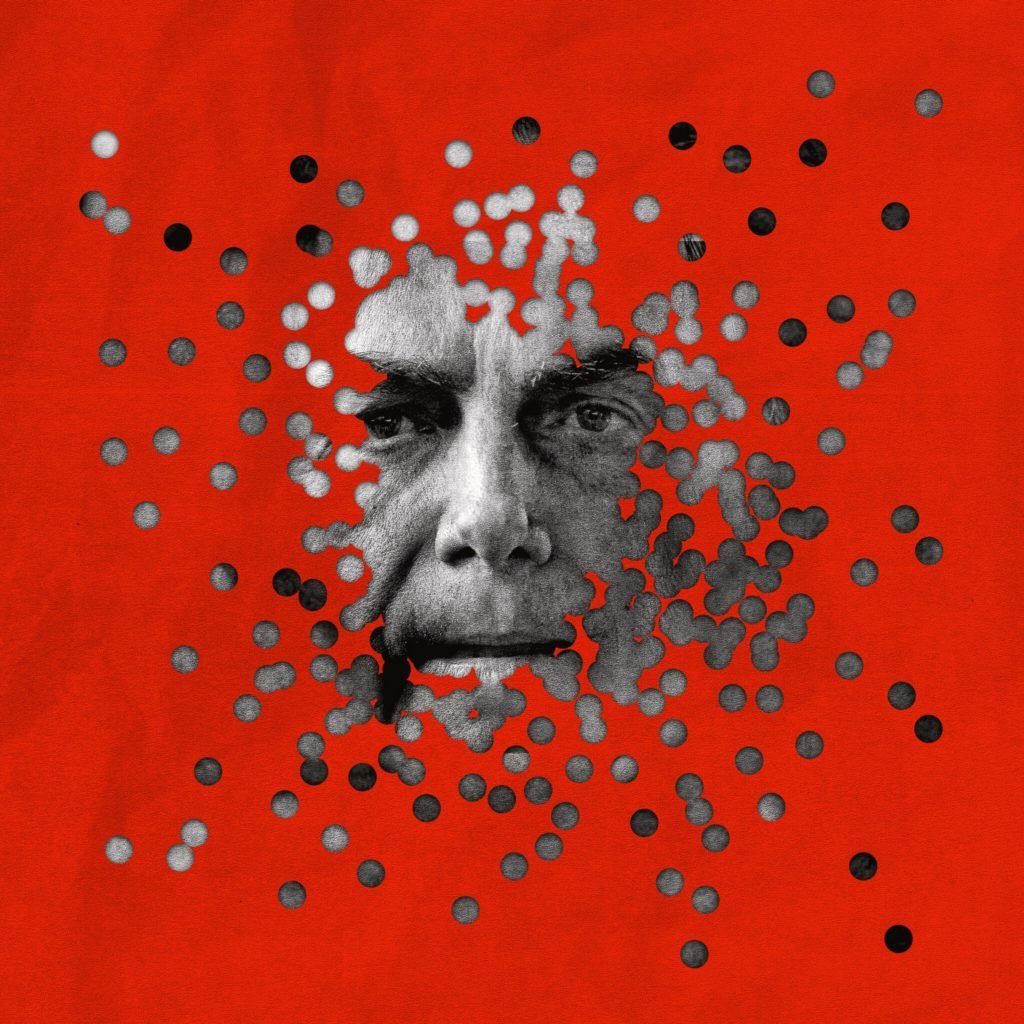

A version of this article appears in print on May 31, 2021, Section A, Page 19 of the New York edition with the headline: Bolsonaro’s Supervillain Plot.