The New York Times

Feb 7, 2022

by Vanessa Barbara

Contributing Opinion Writer

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — Every day, I have the same wish: that my 3½-year-old daughter can get her Covid-19 vaccine.

Last year she seemed to be constantly sick. She was often feverish and coughing, or her nose was runny and her throat sore. She endured four P.C.R. tests and seven rapid tests. (In March one confirmed she had the virus.) We basically spent the year swabbing her tiny nostrils and pulling her out of school every time a student or teacher tested positive.

At times, it could be funny. Just imagine a small child wondering aloud, in the most serious voice, whether she caught the coronavirus because she took off her dinosaur face mask at snack time. But it was mostly exhausting and frightening. Our daughter was building her immune system in the middle of a pandemic, and there was very little we could do about it.

I certainly couldn’t count on our president. True to form, Jair Bolsonaro has been making an already difficult situation worse. After failing to sabotage the vaccination campaigns for adults and teenagers, he’s been concentrating his efforts on undermining vaccination for kids. But against the force of our health system — and Brazilians’ mighty appetite for vaccines — his evil plans have foundered.

Scaremongering is Mr. Bolsonaro’s preferred method. He’s suggested that the vaccine’s collateral effects are “unknown” and that we don’t have an “antidote” to them. Casting himself as a wise uncle, though a totally delusional one, he advised parents to “not be fooled by the propaganda” around children’s vaccination. “My 11-year-old daughter will not be vaccinated,” he informed the country, solemnly. (Pity that poor child.)

But his subterfuge goes further. Though Covid-19 vaccines for children have been proved safe and effective, the government showed no rush to buy them. On Dec. 16, Brazil’s independent Health Regulatory Agency took matters into its own hands and approved the use of Pfizer’s vaccine for children 5 to 11. Mr. Bolsonaro sprang into action: The decision, he said, was “lamentable” and “unbelievable.”

Not content with that dismissal, he then asked for the names of the health officials behind the approval, saying he wanted to release their identities so the public could “come to its own judgments.” This was, to put it lightly, reckless: Over the past few months, the agency’s directors have been receiving hundreds of death threats from people who oppose children’s vaccination. (What’s next? Lynching sanitation workers? Setting fire to penicillin prescriptions?)

As the year ended, the government tried to hold back the campaign by setting up a nonsensical public survey about the issue. It also planned to require every child to have a doctor’s prescription for a vaccine, a demand that governors rejected and was later withdrawn. And the administration’s Health Ministry keeps repeating that vaccinating children is “a parent’s decision,” implying that it might not actually be a good idea. Every step of the way, Mr. Bolsonaro has tried to obstruct children’s access to vaccination, as if catching the coronavirus were preferable.

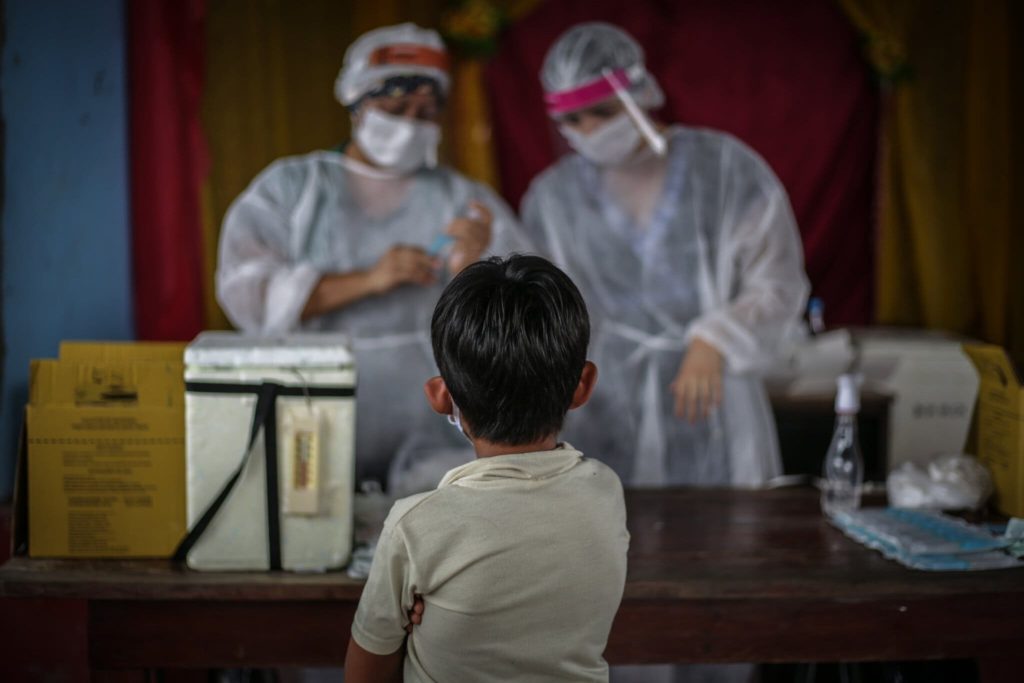

Luckily for us, he failed. Starting Jan. 14, children 5 to 11 began receiving their first shots. Though the number of Pfizer doses available barely covers the country’s 20.5 million children, they are being supplemented by CoronaVac, the Chinese vaccine that has the advantage of being manufactured locally by the Butantan Institute. As with the country’s other vaccination campaigns, we can expect eager uptake.

The president, however, does not seem able to accept that Brazilians are “vaccine maniacs,” as he scornfully put it. Eighty-two percent of Brazil’s population is immunized with at least one dose, and even most anti-vaxxers dutifully take their jabs. Commitment to vaccines comes in strange places. In Rio de Janeiro, a street vendor selling false vaccination certificates — someone you might expect to be unconcerned about people skipping jabs — strongly scolded a prospective buyer. “The right thing to do is take the vaccine, you hear me?” he said. “You must take the vaccine.”

Some countries, to be sure, are coming to different conclusions about the value of vaccinating kids. In Sweden, for example, health officials decided they didn’t see a clear benefit for vaccinating children ages 5 to 11. Mr. Bolsonaro’s main argument, though, is that the death rates don’t justify the effort. Well, according to our Health Ministry, 1,467 children 11 or under have died of Covid-19 — a small fraction of the 632,000 Brazilians who’ve lost their lives but an unacceptable number all the same.

What’s more, vaccination not only prevents suffering among children but also protects the rest of us. Children transmit the virus: As long as they remain vulnerable, so do we all. And right now, amid a record-setting spike of coronavirus cases, Brazilians are very vulnerable indeed. The unvaccinated are particularly at risk, and they are mostly children. Here in São Paulo, there has been a 1,000 percent increase in admissions to pediatric intensive care units in the past month.

So the start of Brazil’s vaccination campaign for children over 5 was a source of happiness for almost everybody — the president excepted, of course. Most schools will resume in-person classes in February, after the summer break, and it will be a profound relief to see millions of kids partly immunized.

My daughter won’t be one of them: She’s still too young to receive her shots. But as a family, we’re feeling, for the first time in a while, cautiously optimistic. Mr. Bolsonaro’s efforts to subvert our health system have mostly failed. Each one of the president’s tantrums is a sign of that failure — and, for us, a cause for celebration.

A version of this article appears in print on Feb. 9, 2022, Section A, Page 19 of the New York edition with the headline: Bolsonaro’s Latest Sabotage Efforts Have Failed