A liderança catastrófica do presidente brasileiro foi minuciosamente exposta

The New York Times

28 de outubro de 2021

por Vanessa Barbara

Contributing Opinion Writer

SÃO PAULO, Brasil — Se meu país tivesse dado uma resposta apenas mediana à pandemia, mais de 400 mil brasileiros estariam vivos. Essa é a dura conclusão do epidemiologista Pedro Hallal, cujo depoimento, ao lado de muitos outros, é registrado no relatório final sobre a gestão do governo no combate à Covid-19. Divulgado na semana passada, é o ápice de uma envolvente Comissão Parlamentar de Inquérito que durou meses.

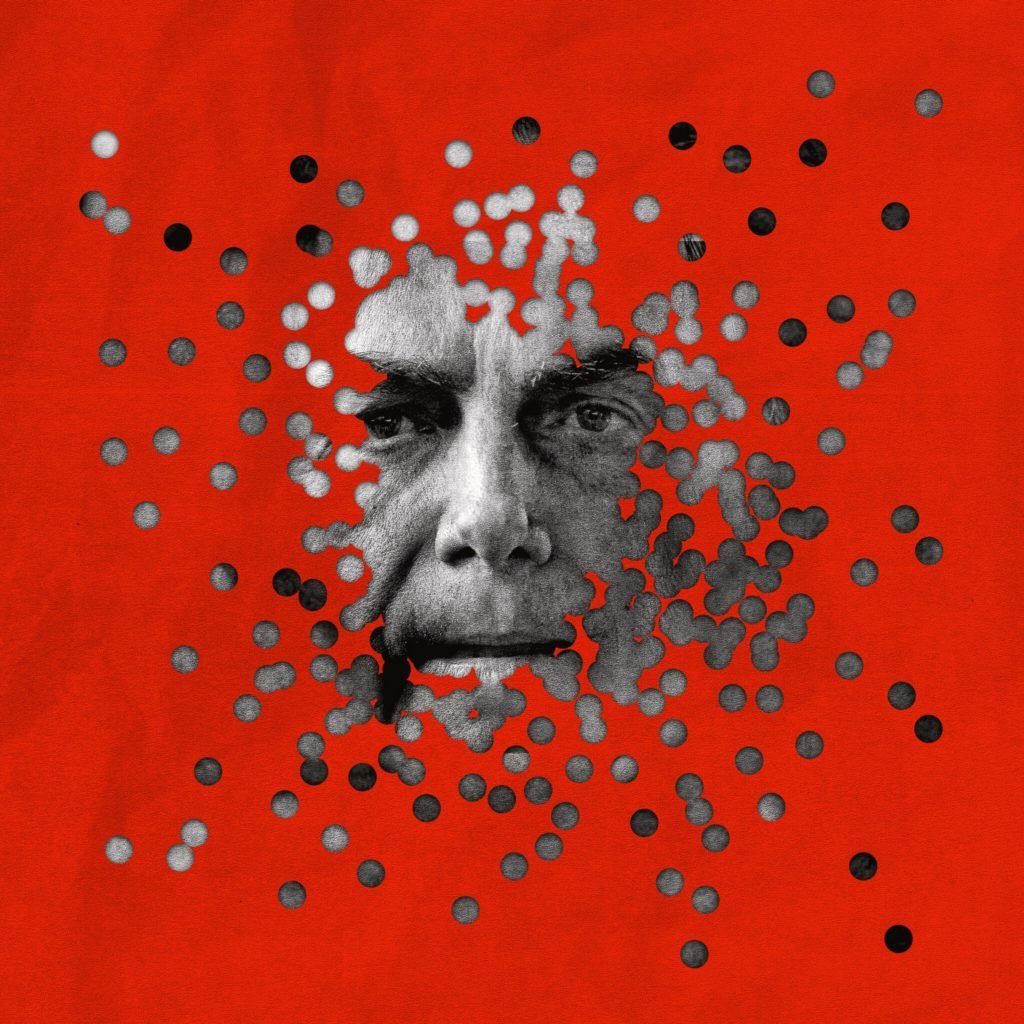

É claro que não sabemos exatamente quantas das 606 mil mortes no país poderiam ter sido evitadas: Hallal faz apenas uma estimativa. Mas a verdade é que não temos um presidente mediano. Nem mesmo um presidente levemente ruim. Temos Jair Bolsonaro, um homem que insiste em dizer que as principais vítimas da Covid-19 foram “os obesos e quem estava apavorado.”

Já era hora de documentarem o catastrófico comando do país exercido por Bolsonaro ao longo da pandemia, e o relatório de 1.288 páginas faz exatamente isso. (Eu li e ainda estou queimando de raiva.) Minuciosamente elaborado, o documento detalha como Bolsonaro ajudou ativamente na disseminação do vírus, não importando qual o custo em vidas humanas. E recomenda que ele seja indiciado por nove crimes, incluindo emprego irregular de verbas públicas, violação de direitos sociais e, o mais grave de todos, crimes contra a humanidade.

Produto de seis meses de trabalho de um comitê especial do Senado, o documento é um esforço bem-vindo de prover os brasileiros de um princípio de responsabilização. Mas possivelmente não é nada além disso: é improvável que Bolsonaro, protegido por um amigável procurador-geral, tenha de eventualmente enfrentar as acusações apontadas contra ele. Cabe agora a organismos internacionais, como o Tribunal Penal Internacional, fazê-lo responder por seus atos. Os brasileiros terão de continuar esperando por justiça e restituição verdadeiras.

O relatório decerto não irá refrear o comportamento do presidente. Bolsonaro o desdenhou na semana passada, ao declarar: “Sabemos que fizemos a coisa certa desde o primeiro momento.” Então ele continua sabotando as medidas para conter a transmissão da Covid-19, como uso de máscaras, distanciamento social e testagem em massa. Ainda promove o “tratamento precoce” com medicamentos ineficazes como a hidroxicloroquina, e diz publicamente que não vai ser vacinado. (Em dezembro, ele comentou que teve “a melhor vacina: foi o vírus.”) Na semana passada, chegou a sugerir que pessoas totalmente imunizadas são mais vulneráveis ao H.I.V.

O empenho de Bolsonaro com as fake news é capturado por inteiro no relatório. Ao lado de seus três filhos mais velhos e outros membros do alto escalão do governo, ele usou o poder estatal para fazer jorrar desinformações. A Secretaria Especial de Comunicação Social (Secom), por exemplo, admitiu ter pago influenciadores em mídias sociais para defender remédios ineficazes. E esse mesmo setor celebrou o fato de que o Brasil era um dos países com o maior número de “curados” da Covid-19. (O que é basicamente dizer que o Brasil tem uma das maiores taxas de infecção — dificilmente um motivo para se gabar.)

O documento está repleto de revelações e anedotas macabras, incluindo aquele que é um dos meus favoritos entre os depoimentos bizarros de um membro do governo. (É difícil escolher, eu admito.) Em uma entrevista para uma rádio em março de 2021, Onyx Lorenzoni, então ministro da Secretaria-Geral da Presidência da República, disse que os lockdowns não eram eficientes para reduzir a disseminação do vírus. Por quê? “Alguém consegue impedir que nas áreas urbanas o passarinho, o cão de rua, o gato, o rato, a pulga, a formiga, o inseto, eles se locomovem? Alguém consegue fazer o lockdown dos insetos? É obvio que não. E todos eles transportam o vírus.”

Mas por trás das anedotas há um relato aterrador da aparente falsidade e corrupção do governo. Por exemplo: o governo atrasou a compra de centenas de milhões de doses de vacina oferecidas por fontes legítimas enquanto supostamente tentava negociar uma vacina não aprovada (e superfaturada) com intermediários obscuros. Bolsonaro foi informado sobre irregularidades na negociação, mas não há evidências de que ele tenha alertado a polícia a respeito.

Pior: aparentemente o governo fez um pacto com a Prevent Senior, uma grande operadora privada de saúde, para produzir dados sobre a eficácia da hidroxicloroquina e outros remédios não comprovados cientificamente para o tratamento da Covid-19. Doze médicos denunciantes acusaram a empresa de testar remédios sem o consentimento dos pacientes e sem a devida autorização da Comissão de Ética. (A Prevent Senior nega todas as acusações.) Esse tenebroso experimento humano se deu, segundo o relatório, com a aprovação do presidente e membros do governo federal.

Na terça-feira, o relatório foi aprovado em uma votação no Senado. “Há um homicida homiziado no Palácio do Planalto,” disse o senador Renan Calheiros, principal responsável pelo documento, ao final da sessão. Foi uma vitória, mas poderia ter sido maior: o rascunho inicial propunha que Bolsonaro fosse indiciado por homicídio e genocídio contra os indígenas, que foram particularmente afetados pelo vírus, mas essas acusações foram mais tarde removidas. Ainda assim, a aprovação do relatório — que efetivamente acusa um presidente em exercício de crimes contra a humanidade — consiste em uma notável condenação a Bolsonaro.

O parecer também recomenda o indiciamento de duas empresas e 77 outras pessoas, incluindo os três filhos mais velhos de Bolsonaro, dois de seus assistentes, o atual Ministro da Saúde (e seu antecessor), um punhado de outros ministros, alguns deputados federais, o antigo chefe da Secom, o presidente do Conselho Federal de Medicina, e os donos e o diretor executivo da Prevent Senior. Toda uma galeria de malfeitores pode ser chamada a responder por seus pecados.

Mas é improvável que isso vá acontecer. Ainda que o documento seja algo a celebrar, infelizmente não é o suficiente para que Bolsonaro e seus aliados tenham de responder por suas ações. Uma ação penal precisa ser instaurada pelo procurador-geral da República, Augusto Aras, que foi indicado pelo próprio presidente e é considerado seu aliado. É difícil imaginar que isso ocorra.

Minha tendência é pensar que a história irá condenar Bolsonaro e seus comparsas pelos crimes horrendos cometidos contra a nossa população, e por nos fazer cobiçar um governo mediano. Mas isso é para o futuro. No presente, tenho um único desejo: que o Tribunal Penal Internacional dê uma boa olhada nesse relatório, com os meus cumprimentos.