New York Review of Books (Daily)

Jun. 10, 2020

SÃO PAULO—“So what? I’m sorry. What do you want me to do?”

So said Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, on April 28 when a reporter pointed out that the country’s toll from Covid-19 had just surpassed China’s—reaching the grim milestone of 5,000 deaths. By the end of May, Brazil had surpassed the half-million mark for coronavirus cases, becoming the world’s No. 2 hotspot for the disease, behind only the United States; it has now topped 38,000 deaths. On Saturday, Bolsonaro’s government stopped publishing official statistics about the country’s outbreak.

“So what?” might sum up why Brazil’s response to the pandemic has been so catastrophic: I’m talking not only about the scorn with which Bolsonaro greeted the news of thousands of deaths, but also about the fact that he appears to think there should be no response at all. “What do you want me to do?” he asks, as if he wasn’t the president of the country.

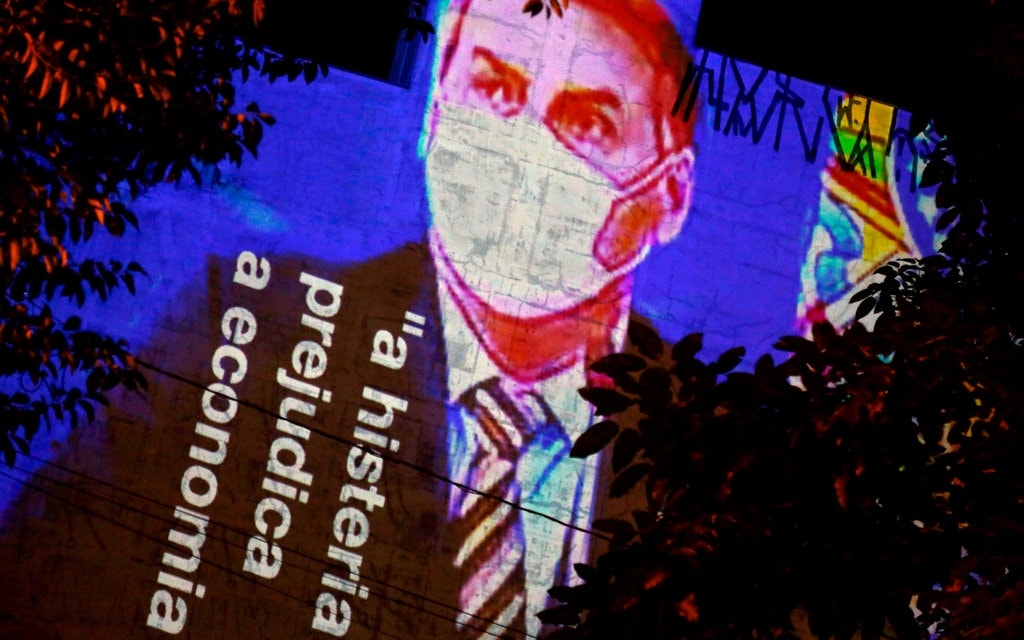

Well, at least he was conceding that something was really going on. At first, he simply denied the severity of the outbreak, saying that it was overblown and “a fantasy.” In a television interview on March 15, he suggested that we shouldn’t buy into this neurosis: “Other viruses have killed many more than this one and there wasn’t all this commotion. Surely there is an economic incentive to create all that hysteria,” he declared.

That month, he foolishly predicted that Covid-19 would kill fewer people in Brazil than the H1N1 flu did last year (under eight hundred). “People will soon see that they were tricked by governors and much of the media when it comes to the outbreak,” he said.

Later that month, twenty-three members of the presidential delegation Brazil sent to the US tested positive for the coronavirus. The sixty-five-year-old president himself tested negative, according to unattributed reports. Then, in a televised address to the nation on March 24, Bolsonaro said his “athletic background” meant that if he was infected by the virus, he wouldn’t have to worry. “I wouldn’t feel anything or at the very worst it would be like a little flu or a bit of a cold,” he said, an especially egregious statement amid many such embarrassments.

On that occasion, he also condemned governors and mayors who enforced social distancing measures. “Our lives have to continue,” he said. “We must, yes, get back to normal.” Ignoring all public health guidance—and against the advice of his own minister of health, Luiz Henrique Mandetta—Bolsonaro argued that keeping the economy open was more important than trying to contain the spread of the virus. In his opinion, 70 percent of the population would get infected anyway, so it might be wiser just to let things run their course.

The president likes to broadcast his message by his actions also, openly defying social-distancing measures whenever possible. On March 29, when Brazil’s death toll reached 139 people, he went for an idle stroll around the suburbs of Brasília. He personally greeted street vendors and people at bakery shops and drugstores, without wearing a protective mask. When reporters confronted him with questions about the coronavirus, he replied: “That’s life. We will all die one day.”

*

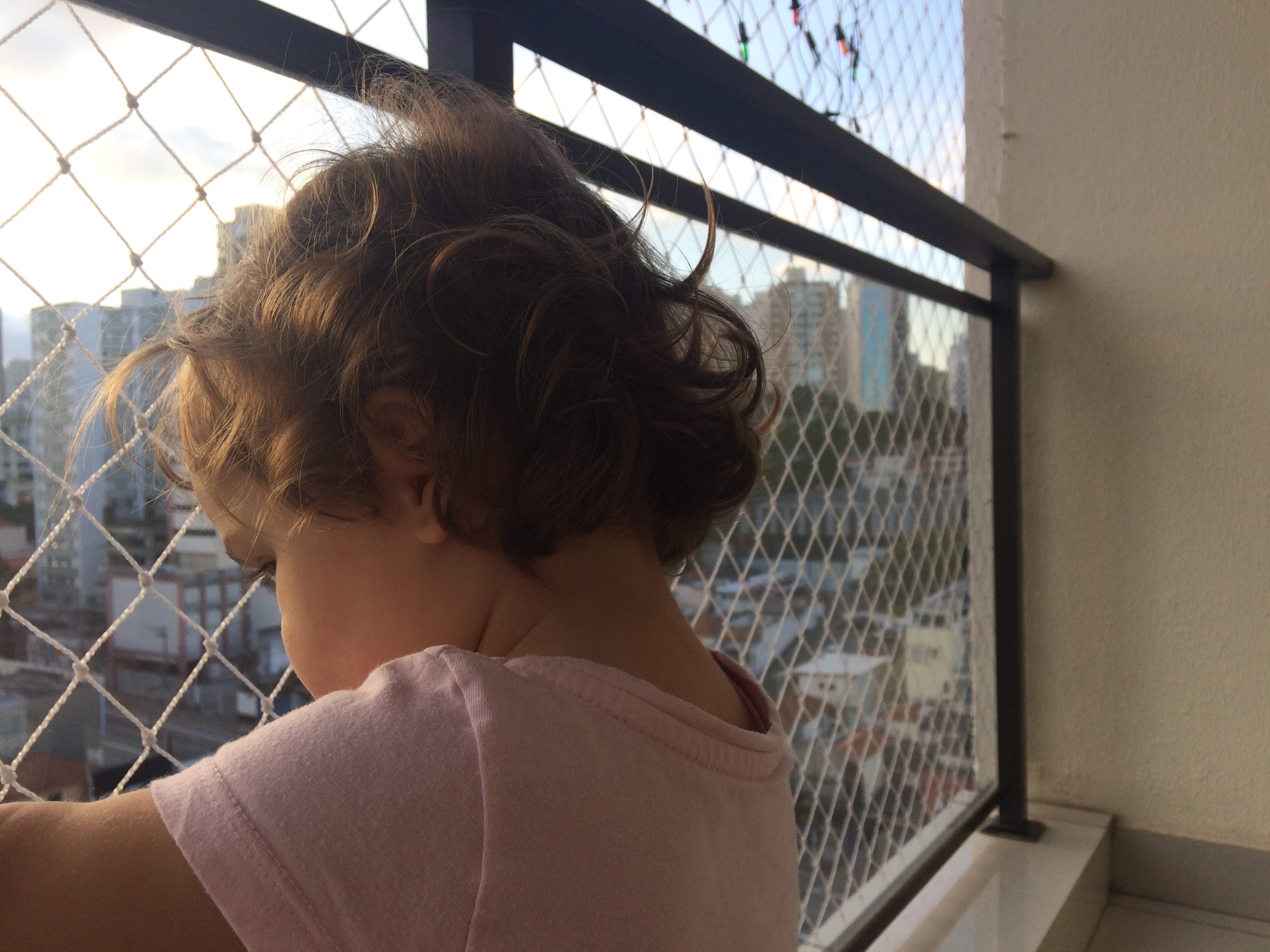

Here in São Paulo, the hardest-hit state in Brazil, less than half of the population are adhering to social-distancing rules. (A rate of 70 percent is needed to stop the virus spread, according to the state’s government.) My husband, our two-year-old-daughter, and I have been following social-distancing measures for eighty-five days now; the only contact we ever have with the rest of the family is through video calls. We take sanitary precautions. We cut our own hair. We leave the house only once in a while for reasons of absolute necessity—to go to the supermarket or the drugstore.

On these rare occasions, though, we see lots of people gathered on the sidewalks, drinking beer, and chatting. Others run shop errands, ducking in and out under the half-closed stores’ shutters. According to media reports, many beauty parlors and barber’s shops are open throughout the city. An evangelical church downtown is not only holding services for thousands of people but also selling magic bean seeds that purportedly cure Covid-19.

While it’s true that some people don’t have any choice but to keep going to work, others just choose to imitate the president: they have responded to the pandemic with an emphatic shrug.

*

Bolsonaro supports “vertical interdiction,” which stipulates mandatory quarantine only for those people most vulnerable to the coronavirus: the elderly, people with chronic diseases, and the immuno-compromised. The rest can go on with their lives, according to this theory, eventually catching the virus and developing a mild infection, from which they would (also theoretically) recover and gain natural immunity. This, in turn, would benefit the society as a whole by entrenching so-called “herd immunity.”

The strategy has since been dismissed by health experts and, well, by reality. While Covid-19 has proven more lethal for the elderly, it can be fatal to younger, healthy people, too. In Brazil, 30 percent of those killed by the virus were under sixty. Thirty-five percent had no comorbidity. Hospitalization rates are very high even among younger patients, which is why the demand for critical care services rapidly overwhelms supply. Death rates of between 1 and 3 percent means that Brazil still runs the risk of suffering more than 1.5 million deaths, considering that up to 70 percent of the population could get infected. In that light, testing the “herd immunity” theory with a new, unpredictable virus is wildly irresponsible.

But in Bolsonaro’s Brazil, we have no use for facts and logic, since the president himself is very likely unsure what “vertical interdiction” even means. He has been endorsing the idea as if it was a magical solution that he alone was able to offer: locking away the most vulnerable among us while the rest resume their business. As a matter of fact, I think he is ready to accept as truth any proposition that ends with “… resume their business.” What comes before this hardly matters.

He views the situation as a simple tradeoff between saving lives of the elderly and preserving jobs for the young and healthy. This is an idea both hideous and wrong. Many economists agree that hasty moves to reopen the economy can only increase the risks for vulnerable workers without generating meaningful growth; in the end, that would serve to needlessly sacrifice tens of thousands of lives, at huge cost. Economic recession will happen anyway. We can only choose how long and lethal the health crisis will be.

In his drive to reopen the economy, Bolsonaro often doesn’t even pretend to be plausible: two months ago, for example, he brushed off the possibility that the country could face a situation as harsh as the United States by claiming Brazilians can “swim in raw sewage” and “they don’t catch a thing.” And now we’re resolutely following in the US’s footsteps.

Brazil’s president also followed his American counterpart in advocating for the widespread use of hydroxychloroquine (or chloroquine) as a treatment for Covid-19, although no study to date has proven the efficacy and safety of both drugs. Nothing can deter him from his unfounded resolve.

*

So far, during the coronavirus outbreak, Jair Bolsonaro has attended protests held by anti-shutdown supporters; he has ridden a jet ski on a lake; he has joined a pro-government rally on horseback; he has wiped his nose on his wrist before greeting an elderly woman. As the virus spread, he kept shaking hands and taking selfies with his supporters. “No one is going to curtail my freedom to come and go,” he said. Sometimes, he wears a mask down around his chin.

On April 12, when Brazil’s death toll reached 1,200 deaths, the president announced that “this issue of the virus” was “starting to go away.” A few days—and seven hundred deaths—later, on April 16, he fired health minister Mandetta, who had been arguing for a science-based strategy that comprised strict social distancing measures. “I know that life is priceless,” said the president. “But the economy and employment must return to normal.”

On April 24, Bolsonaro’s most popular cabinet member, justice minister Sergio Moro, resigned from his post, accusing the president of trying to replace the federal police chief in order to shield his sons from criminal investigations. (The Supreme Court has already opened an investigation into the president’s actions.) In response, Bolsonaro delivered a lengthy, embittered televised address in which he complained that Moro had ignored him once at an airport, some time before the presidential campaign. He went on to proclaim that he had turned off the heating in the presidential swimming pool in order to save public money and disclosed that his wife’s grandmother had once been arrested for drug trafficking. Yes, it was really that random.

He mentioned the coronavirus outbreak only once, and that tangentially. By then, Brazil had registered 3,704 deaths from the disease.

When, on April 29, the president finally expressed public regret for the deaths, he added: “We express our solidarity to those who have lost loved ones, many of whom were elderly. But that’s life, it could be me tomorrow.”

*

Jair Bolsonaro has once compared the coronavirus to the rain: “You will get wet, but you are not going to drown,” he said in a television interview last April. Rain is a natural phenomenon beyond human control; in Bolsonaro’s opinion, even a president is helpless in the face of force majeure. Let’s set aside the existence of umbrellas, roofs, and policies for flood mitigation. Let’s ignore that one can learn to predict the changes in weather and prepare for storms.

He added, in that same interview, that “in some cases, regretfully, there will be drowning”—but only if the person has another health problem or is somehow “weaker.” He further explained: “Sometimes a person may live in penury, so they are weak by nature, let’s put it this way, for the lack of adequate food. Those are the ones who suffer the most [from the virus].”

Coincidently or not, many of those people are the very ones for whom Bolsonaro has always shown most contempt. Among them, indigenous people, quilombolas (descendants of groups of escaped slaves), homeless people, riverside dwellers, inhabitants of favelas, migrants, and refugees. Rio’s favelas have recorded more deaths from the virus than fifteen Brazilian states. In the main cemetery of Manaus, in the Amazon region, bulldozers have begun to dig mass graves. The region is one of the most affected by the outbreak, as it is also one of the poorest. It has twelve of the twenty cities with the highest incidence of Covid-19 cases in the country, and five out of the ten municipalities with the highest mortality rate. By now, the disease has reached more than seventy indigenous communities, killing at least 147 people.

Not even children have been spared: at least forty-one babies and thirty-five children under nine years old have died. Most of them lived in the poorest North and Northeast regions of the country.

*

In the weeks following Bolsonaro’s interview, Brazil’s death rate rose to the highest levels in the world. On May 11, after the country topped 11,500 Covid-19 deaths, Bolsonaro issued a decree classifying gyms and hair salons as essential services that could stay open through the outbreak. A few days later, he signed another decree, this one exempting public officials—himself included—from any liability for their responses to the pandemic.

On May 15, Brazil’s newly appointed health minister Nelson Teich announced he was quitting, after less than a month on the job. He had been refusing to endorse the widespread use, advocated by the president, of anti-malarial drugs for patients with Covid-19.

Since then, Eduardo Pazuello, an active-duty army general with no medical background, has been serving as Brazil’s interim health minister. He promptly issued official guidelines expanding the prescription of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for coronavirus patients, despite, again, the lack of scientific evidence of their efficacy.

Soon, Brazil overtook Russia as the country with the second-highest total number of coronavirus infections worldwide, lagging only behind the United States. On May 22, the confirmed case tally reached 330,890, with more than 21,000 deaths. As of June 9, the death tally reached 37,000. The true numbers are likely to be much higher, however, because the country has not carried out widespread testing. A study by the Federal University of Pelotas concluded that the country’s caseload could be seven times the official number.

As a consequence, both public and private hospitals have been pushed to the brink of collapse in many states. On top of that, more nurses have died here than anywhere else on the world; the death toll is also high among doctors.

And yet, Bolsonaro has been somewhat successful at shifting the blame away from himself. Despite rising rejection rates, he still maintains a stable support base of about a third of the population. More recently, the federal government have forged an alliance with powerful centrist parties, thus shielding Bolsonaro from impeachment attempts against him.

Experts believe that the coronavirus outbreak has not yet reached a peak here. According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, the virus is predicted to have killed more than 125,000 people in the country by early August. Yet the president’s response is still the same shrug: “I regret each of the deaths, but that’s everyone’s destiny.”

For his handling of this crisis, Jair Bolsonaro will, at some point, surely face a reckoning of his own with destiny. That is our only hope.